Foxy Production presents Global Tone, a solo exhibition by Michael Wang. Wang examines episodes from the history of the 20th century in which systems—political, scientific, artistic —collide. At their intersection is a transfer of energy, disruption, and feedback. The global effects of these interactions trace a chain of relationships among history, politics, aesthetics, biology, physics, and popular culture.

Individual works look to iconic figures from the political and artistic spheres: Jacqueline Kennedy, Hermann Göring, and Isamu Noguchi. Instead of treating them in a narrative vein as heroes, villains, or geniuses, they are understood as neutral points at which a range of natural and cultural forces coincide.

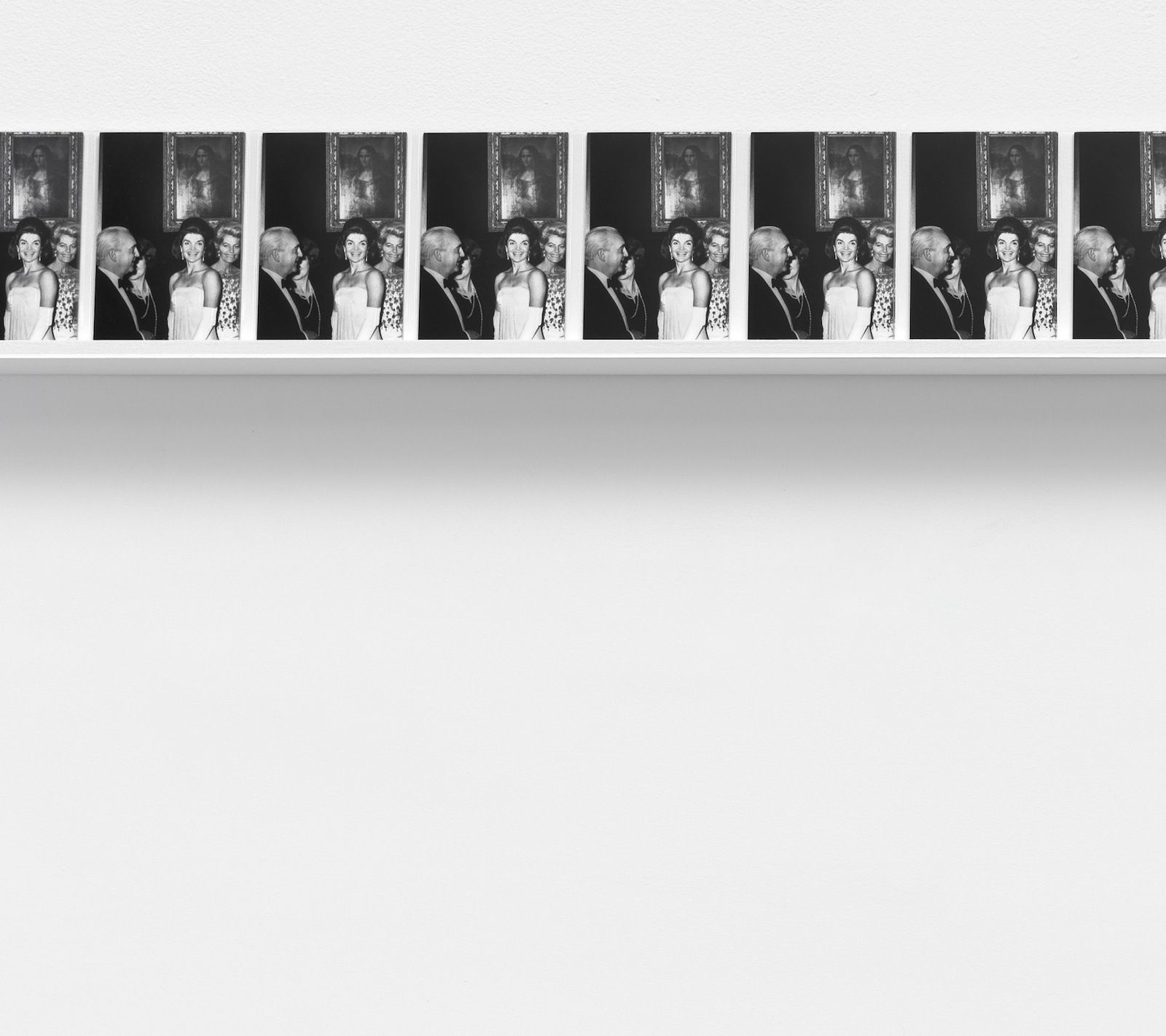

Kennedy puts art in the service of politics when she arranges the loan of the “Mona Lisa” from Paris to Washington to solidify Franco-American relations at the height of the Cold War. Göring aligns biology with national destiny when he successfully interbreeds American and European bison to strengthen the diminished genetic stock of the European herd. Noguchi equates monument-building with the reconstruction of a state when he proposes—unsuccessfully—to memorialize the victims of the atomic bomb at Hiroshima with a granite cenotaph.

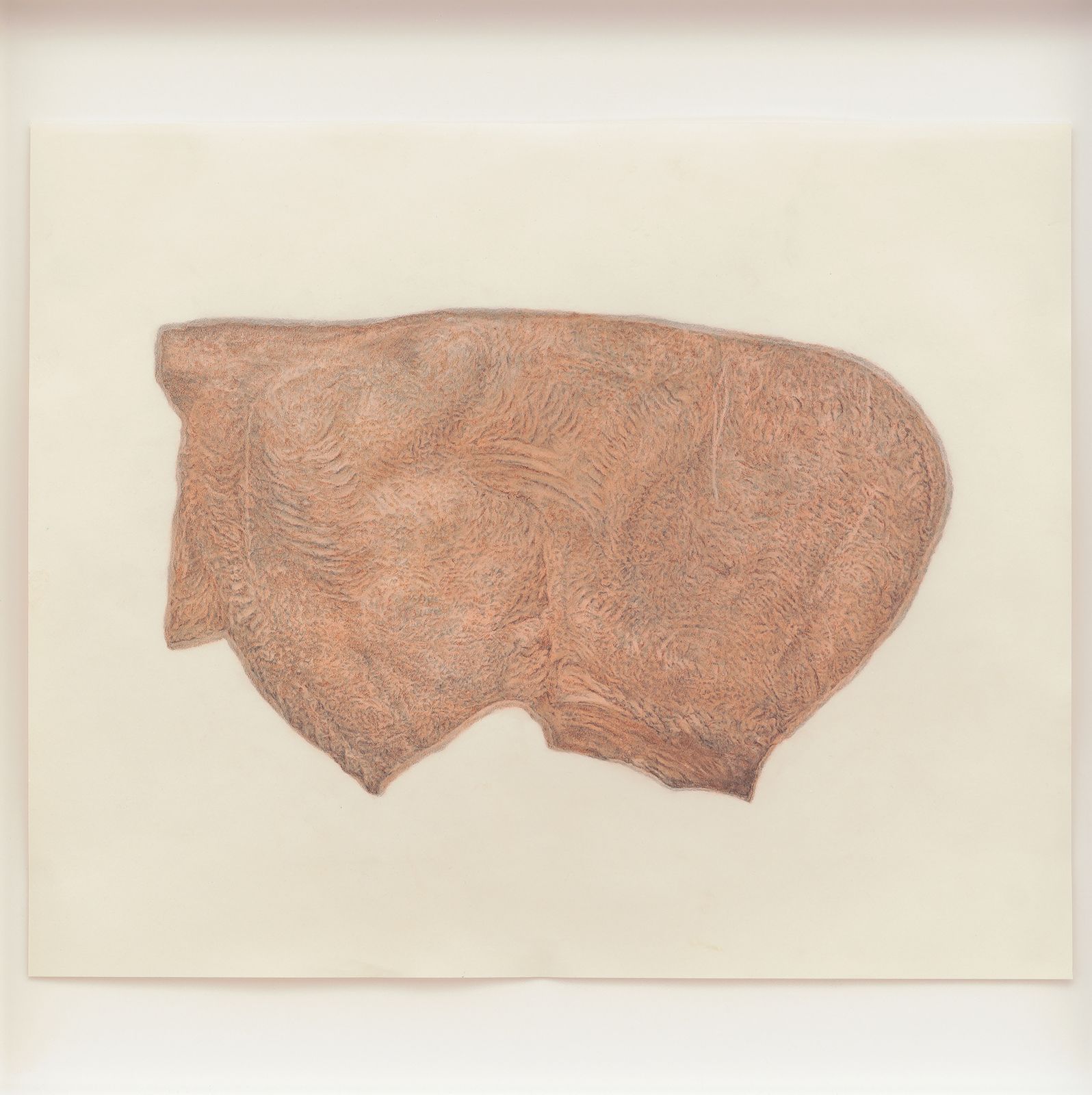

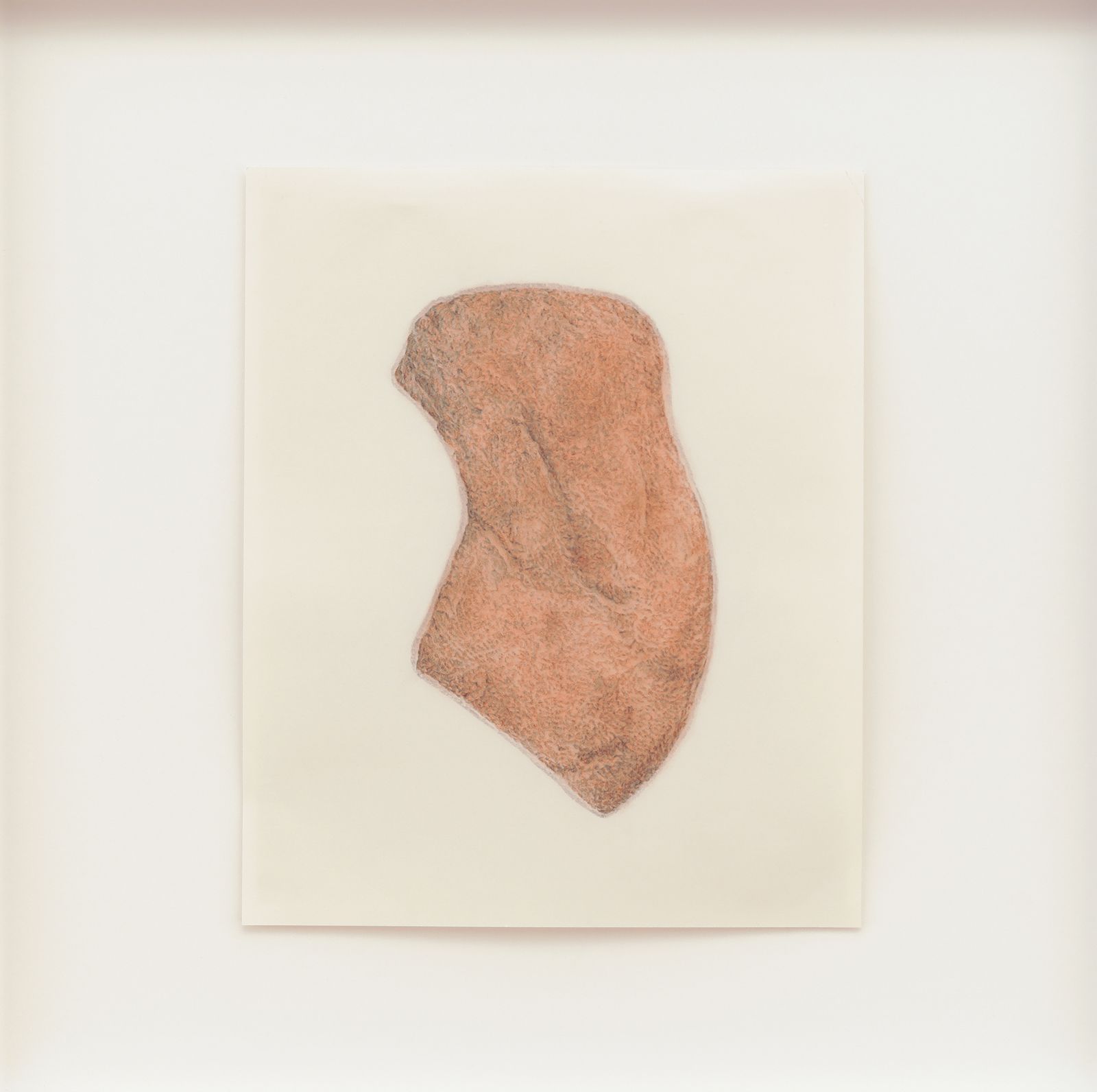

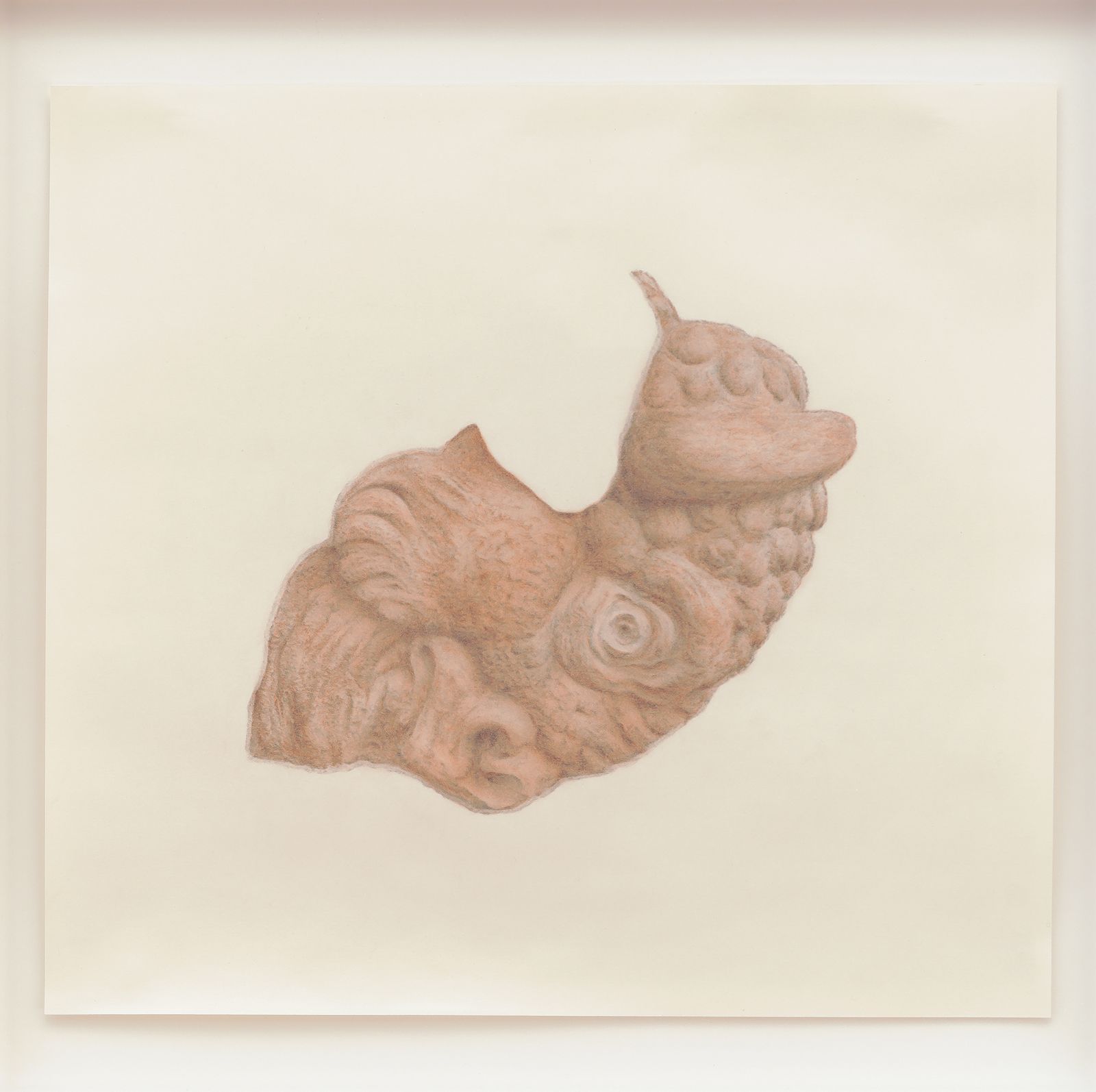

In each encounter—between the Old World and the New, East and West—a singular image or object emerges from the historical cacophony: the beaded gown that Kennedy wears to the opening of the “blockbuster” Mona Lisa show; the monument in Meissen stoneware that Göring commissions to commemorate the success of his bison breeding program; Noguchi’s one-fifth scale cenotaph in polished black stone.

These objects do not arrive into the present unaltered. Kennedy’s gown has outlived the event that was, originally, its sole destiny. Safeguarded in the holdings of the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum, it is now treated, like the Mona Lisa herself, with a conservator’s care. The Mona Lisa Gown (2013) amplifies the veneration afforded this object. Envisioned as the centerpiece of a traveling exhibition, the gown is untethered from its specific historical context to become a mutable, global symbol.

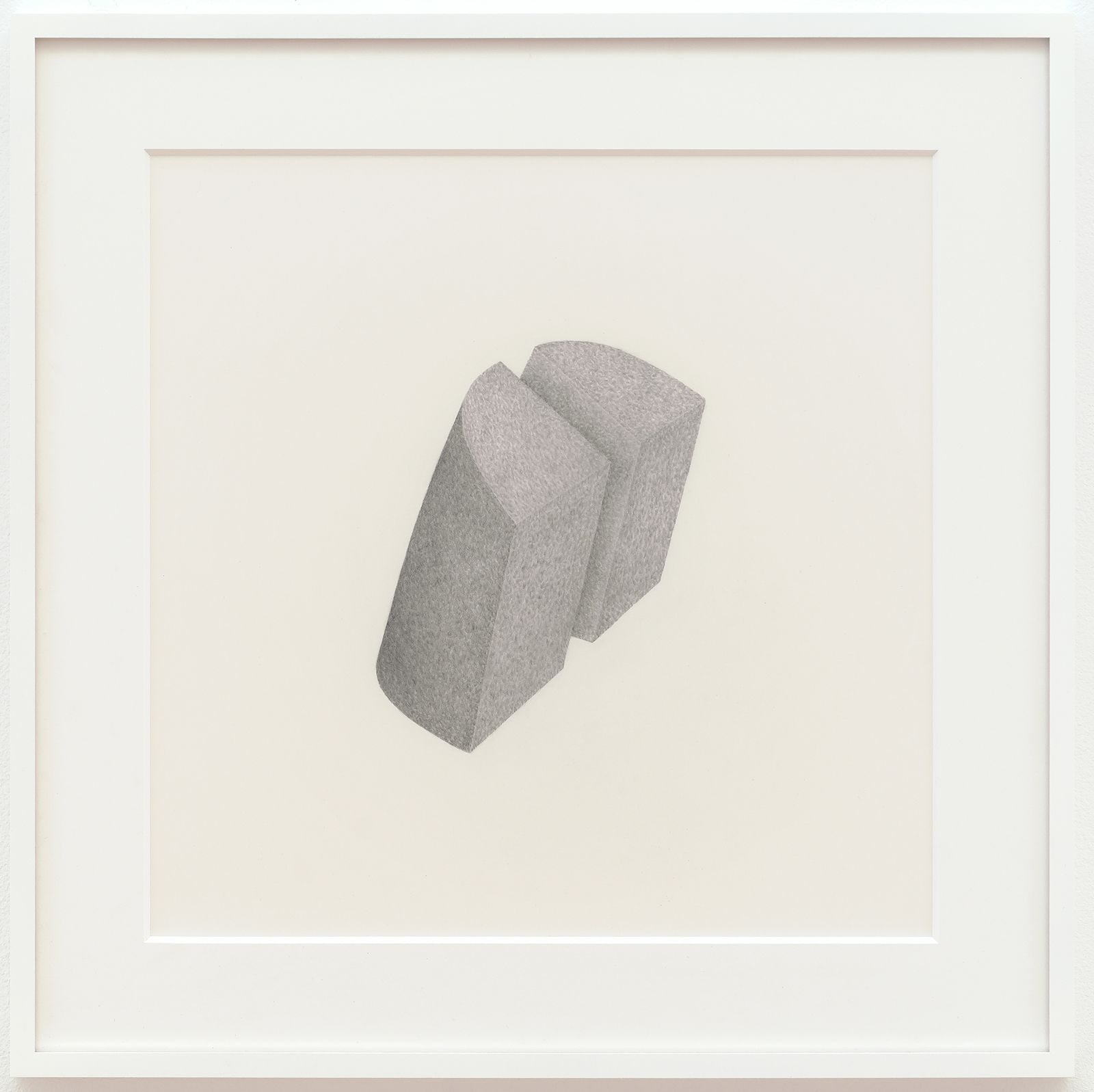

After the war, Göring’s sculpture is cut into pieces and buried. In the mid-1990s, it is unearthed, re-assembled, and put on public display in a small forest town. In 1982, thirty years after submitting his original proposal to the city of Hiroshima, Noguchi returns to his cenotaph, re-making the original plaster model in granite at a much larger scale. In the exhibition’s drawings, these sculptures are subject to invisible forces of dissolution. Göring’s sculpture comes apart at its mortar seams. Noguchi’s arch explodes into its beveled stone blocks.

Running beneath each of the works is a general movement of strategic diffusion: a bleeding outwards. Each individual gesture of fragmentation, transport, or exchange becomes part of a larger trend toward global dispersal—the imagined limit of which would be a state of global equilibrium, a global average.

A cast of professional female models, invited to the show’s opening, represent this future world in which the human species itself arrives at a stable state of equilibrium. A casting director has selected only models whose complexion matches a current “global average” skin tone—a specific color calculated with the assistance of biological anthropologists and a computer-imaging specialist. In a nearly invisible performance, these uniformly bronze models will mix among the other gallery-goers. Extending the logic of assimilation to its ultimate conclusions, they are a vision of a future, perfected humanity: 21st century globalization’s answer to 20th century eugenics.

CREDITS:

Michael Wang, Global Tone (Poster), 2013 (Photo: Danielle Levitt.) All other photography: Mark Woods.